I demand whether all wars, bloodshed and misery came not

upon the creation when one man endeavoured to be a lord over

another? ... And whether this misery shall not remove... when all

the branches of mankind shall look upon the earth as one

common treasury to all.

To him she was a fragmented commodity whose feelings and

choices were rarely considered: her head and her heart were

separated from her back and her hands and divided from her

womb and vagina. Her back and muscle were pressed into field

labor... her hands were demanded to nurse and nurture the white

man .... [H]er vagina, used for his sexual pleasure, the gateway

to the womb, which his place of capital investment - the capital

investment being the sex-act and the resulting child the

accumulated surplus....

>>

Albrecht Durer, The Fall of Man< (1510).

This powerful scene, on the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the

Garden of Eden, evokes the expulsion of the peasantry from its

common lands, which was starting to occur across western

Europe at the very time when Durer was producing this work.

Introduction

Footnotes 1 & 2

1. Peter Blickle objects to the concept of a “peasant war” because of the social composition of this revolution, which included many artisans, miners, and intellectuals

among its ranks. The Peasant War combined ideological sophistication, expressed

in the twelve articles’ which the rebels put forward, and a powerful military organization. The twelve articles included: the refusal of bondage, a reduction of the

tithes, a repeal of the poaching laws, an affirmation of the rights to gather wood, a

lessening of labor service^, a reduction of rents, an affirmation of the rights to use

the common, and an abolition of death taxes (Bickle 1985: 195-201). The exceptional military prowess demonstrated by the rebels depended in part on the participation of professional soldiers in the revolt, including the Landsknechte — the

famous Swiss soldiers who, at the time, were the elite mercenary troops in Europe.

The Landsknechte headed the peasant armies, putting their military expertise at

their service and, in various occasions, refused to move against the rebels. In one

case, they motivated their refusal by arguing that they too came from the peasantry

and that they depended on the peasants for their sustenance in times of peace. When

it was clear that they could not be trusted, the German princes mobilized the troops

of the Swabian League, drawn from more remote regions, to break the peasant

resistance. On the history of the Landsknechte and their participation in the Peasant

War, see Reinhard Baumann, I Lanzichenecchi (1994: 237-256).

2. The Anabaptists, politically, represented a fusion of "the late

medieval social movements and the new anti-clerical movement

sparked off by the Reformation." Like the medieval heretics, they

condemned economic individualism and greed and supported a

form of Christian communalism.Their take-over of Munster

occurred in the wake of the Peasant War, when unrest and urban

insurrections spread from Frankfurt to Cologne and other towns

of Northern Germany. In 1531, the crafts took control of the city

of Munster, renamed it New Jerusalem, and under the influence

of immigrant Dutch Anabaptists, installed in it a communal

government based upon the sharing of goods. As Po-Chia Hsia

writes, the records of New Jerusalem were destroyed and its

story has been told only by its enemies.Thus, we should not

presume that events unfolded as narrated. According to the

available records, women had at first enjoyed a high degree of

freedom in the town; for instance, "they could divorce their

unbelieving husbands and enter into new marriages." Things

changed with the decision by the reformed government to

introduce polygamy in 1534, which provoked an "active

resistance" among women, presumably repressed with

imprisonment and even executions (Po-Chia Hsia 1988a: 58-59).

Why this decision was taken is not clear. But the episode

deserves more investigation, given the divisive role that the

crafts played in the "transition" with regard to women. We know,

in fact, that the craft campaigned in several countries to exclude

women from the waged work-place, and nothing indicates that

they opposed the persecution of the witches.

The development of capitalism was not the only possible response to

the crisis of feudal power. Throughout Europe, vast communalistic

social movements and rebellions against feudalism had offered the

promise of a new egalitarian society built on social equality and

cooperation. However, by 1525 their most powerful expression, the

"Peasant War" in Germany or, as Peter Blickle called it, the

"revolution of the common man," was rushed.1

A hundred thousand

rebels were massacred in retaliation. Then, in 1535, "New

Jerusalem," the attempt made by the Anabaptists in the town of

Munster to bring the kingdom of God to earth, also ended in a

bloodbath, first undermined presumably by the patriarchal turn taken

by its leaders who, by imposing polygamy, caused the women

among their ranks to revolt.2

With these defeats, compounded by

the spreads of hunts and the effects of colonial expansion, the

revolutionary process in Europe came to an end. Military might was

not sufficient, however, to avert the crisis of feudalism.

By the late Middle Ages the feudal economy was doomed, faced with

an accumulation crisis that stretched for more than a century. We

deduce its dimension from some basic estimates indicating that

between 1350 and 1500 a major shift occurred in the power-relation

between workers and masters. The real wage increased by 100%,

prices declined by 33%, rents also declined, the length of the

working-day decreased, a tendency appeared toward local self-

sufficiency3.

3. For the rise of the real wage and the fall of prices in England,

see North and Thomas (1973:74). For Florentine wages, see

Carlo M. Cipolla (1994: 206). For the fall in the value of output in

England see R. H. Britnel (1993:156-171). On the stagnation of

agricultural production in a number of European countries, see

B.H. SlicherVan Bath (1963:160-170). Rodney Hilton argues that

this period saw "a contraction of the rural and industrial

economies...probably felt in the first place by the ruling

class....Seigneurial revenues and industrial and commercial

profits began to fall....Revolt in the towns disorganized industrial

production and revolt in the countryside strengthened peasant

resistance to the payment of rent. Rent and profits thus dropped

even further" (Hilton 1985:240-241).

Evidence of a chronic disaccumulation trend in this period is also found in the pessimism of the contemporary merchants and landowners, and the measures which the European states

adopted to protect rackets, suppress competition and force people to

work at the conditions imposed. As the entries in the registers of the

feudal manors recorded, "the work [was] not worth the breakfast"

(Dobb 1963: 54). The feudal economy could not reproduce itself, nor

could a capitalist society have "evolved" from it, for self-sufficiency

and the new high-wage regime allowed for the "wealth of the

people," but "excluded the possibility of capitalistic wealth" (Marx

1909, Vol.I: 789).

It was in response to this crisis that the European ruling class

launched the global offensive that in the course of at least three

centuries was to change the history of the planet, laying the

foundations of a capitalist world-system, in the relentless attempt to

appropriate new sources of wealth, expand its economic basis, and

bring new workers under its command.

5. Critics of Marx's concept of "primitive accumulation" include:

Samir Amin (1974) and Maria Mies (1986). While Samir Amin

focusses on Marx's Eurocentrism, Mies stresses Marx's

blindness to the exploitation of women. A different critique is

found in Yann Moulier Boutang (1998) who faults Marx for

generating the impression that the objective of the ruling class in

Europe was to free itself from an unwanted work-force. Moulier

Boutang underlines that the opposite was the case: land

expropriation aimed to fix workers to their jobs, not to encourage

mobility. Capitalism — as Moulier Boutang stresses — has

always been primarily concerned with preventing the flight of

labor (pp. 16—27).

As we know, "conquest, enslavement, robbery, murder, in brief force"

were the pillars of this process (ibid.: 785). Thus, the concept of a

"transition to capitalism" is in many ways a fiction. British historians,

in the 1940s and 1950s, used it to define a period — roughly from

1450 to 1650 — in which feudalism in Europe was breaking down

while no new social-economic system was yet in place, though

elements of a capitalist society were taking shape. The concept of

"transition," then, helps us to think of a prolonged process of change

and of societies in which capitalist accumulation coexisted with

political formations not yet predominantly capitalistic. The term,

however, suggests a gradual, linear historical development, whereas

the period it names was among the bloodiest and most

discontinuous in world history — one that saw apocalyptic

transformation and which historians can only describe in the

harshest terms: the Iron Age (Kamen), the Age of Plunder (Hoskins),

and the Age of the Whip (Stone). "Transition," then, cannot evoke

the changes that paved the way to the advent of capitalism and the

forces that shaped them. In this volume, therefore, I use the term

primarily in a temporal sense while I refer to the social processes

that characterized the "feudal reaction" and the development of

capitalist relations with the Marxian concept of "primitive

accumulation," though I agree with its critics that we must rethink

Marx's interpretation of it.5

Footnotes 6 & 7

6. As Michael Perelman points out, the term "primitive

accumulation" was actually coined by Adam Smith and rejected

by Marx, because of its ahistorical character in Smith's usage.

"To underscore his distance from Smith, Marx prefixed the

pejorative ‘so-called' to the title of the final part of the first volume

of Capital, which he devoted to the study of primitive

accumulation. Marx, in essence, dismissed Smith's mythical

‘previous' accumulation in order to call attention to the actual

historical experience" (Perlman 1985:25-26).

7. On the relation between the historical and the logical

dimension of "primitive accumulation" and its implications for

political movements today see: Massimo De Angelis, "Marx and

Primitive Accumulation. The Continuous Character of Capital

‘Enclosures'." In The Commoner: www.commoner.org.uk; Fredy

Perlman, The Continuing Appeal of Nationalism. Detroit: Black

and Red, 1985; and Mitchel Cohen, "Fredy Perlman: Out in Front

of a Dozen Dead Oceans" (Unpublished manuscript, 1998).

Marx introduced the concept of "primitive accumulation" at the end of

Capital Volume I to describe the social and economic restructuring

that the European ruling class initiated in response to its

accumulation crisis, and to establish (in polemics with Adam Smith)6

that: (i) capitalism could not have developed without a prior

concentration of capital and labor; and that (ii) the divorcing of the

workers from the means of production, not abstinence of the rich, is

the source of capitalist wealth. Primitive accumulation, then, is useful

concept, for it connects the "feudal reaction" with the development of

a capitalist economy and it identifies the historical and logical

conditions for the development of the capitalist system, "primitive"

("originary") indicating a precondition for the existence of capitalist

relations as much as a specific event in time.7

Marx, however, analyzed primitive accumulation almost exclusively

from the viewpoint of the waged industrial proletariat: the

protagonist, in his view, of the revolutionary process of his time and

the foundation for the future communist society. Thus, in his account,

primitive accumulation consists essentially in the expropriation of the

land from the European peasantry and the formation of the "free,"

independent worker, although he acknowledged that:

The discovery of gold and silver in America, the extirpation,

enslavement and entombment in mines of the aboriginal

population, [of America], the beginning of the conquest and

looting of the East Indies, the turning of Africa into a preserve for

the commercial hunting of black skins, are ... the chief moments

of primitive accumulation ... (Marx 1909, Vol. I: 823).

Marx also recognized that "[a] great deal of capital, which today

appears in the United States without any certificate of birth, was

yesterday in England the capitalised blood of children" (ibid.: 820-

30). By contrast, we do not find in his work any mention of the

profound transformations that capitalism introduced in the

reproduction of labor-power and the social position of women. Nor

does Marx's analysis of primitive accumulation mention the "Great

Witch-Hunt" of the 16th and 17th centuries, although this state-

sponsored terror campaign was central to the defeat of the European

peasantry, facilitating its expulsion from the lands it once held in

common.

In this chapter and those that follow, I discuss these developments,

especially with reference to Europe, arguing that:

- The expropriation of European workers from their means of

subsistence, and the enslavement of Native Americans and

Africans to the mines and plantations of the "New World," were

not the only means by which a world proletariat was formed and

"accumulated."

- This process required the transformation of the body into a

work-machine, and the subjugation of women to the

reproduction of the work-force. Most of all, it required the

destruction of the power of women which, in Europe as in

America, was achieved through the extermination of the

"witches."

- Primitive accumulation, then, was not simply an accumulation

and concentration of exploitable workers and capital. It was also

an accumulation of differences and divisions within the working

class, whereby hierarchies built upon gender, as well as "race"

and age, became constitutive of class rule and the formation of

the modern proletariat.

- We cannot, therefore, identify capitalist accumulation with the

liberation of the worker, female or male, as many Marxists

(among others) have done, or see the advent of capitalism as a

moment of historical progress. On the contrary, capitalism has

created more brutal and insidious forms of enslavement, as it

has planted into the body of the proletariat deep divisions that

have served to intensify and conceal exploitation. It is in great

part because of these imposed divisions — especially those

between women and men — that capitalist accumulation

continues to devastate life in every corner of the planet.

Capitalist Accumulation and the Accumulation of

Labor in Europe

Footnotes 8 & 9

8. For a description of the systems of the encomienda, mita, and

catequil see (among others) Andre Gunder Frank (1978),45;

Steve J. Stern (1982); and Inga Clendinnen (1987). As described

by Gunder Frank, the encomienda. was "a system under which

rights to the labor of the Indian communities were granted to

Spanish landowners." But in 1548, the Spaniards "began to

replace the encomienda de servido by the repartimiento (called

catequil in Mexico and mita in Peru), which required the Indian

community's chiefs to supply the Spanish juez repartidor

(distributing judge) with a certain number of days of labor per

month.... The Spanish official in turn distributed this supply of

labor to qualified enterprising labor contractors who were

supposed to pay the laborers a certain minimum wage"

(1978:45). On the efforts of the Spaniards to bind labor in Mexico

and Peru in the course of the various stages of colonization, and

the impact on it of the catastrophic collapse of the indigenous

population, see again Gunder Frank (ibid.: 43-49). ↩

9. For a discussion of the "second serfdom" see Immanuel

Wallerstein (1974) and Henry Kamen (1971). It is important here

to stress that the newly enserfed peasants were now producing

for the international grain market. In other words, despite the

seeming backward character of the work-relation imposed upon

them, under the new regime, they were an integral part of a

developing capitalist economy and international capitalist division

of labor.

Capital, Marx wrote, comes on the face of the earth dripping blood

and dirt from head to toe (1909, Vol. I: 834) and, indeed, when we

look at the beginning of capitalist development, we have the

impression of being in an immense concentration camp. In the "New

World" we have the subjugation of the aboriginal population to the

regimes of the mita and cuatelchil8 under which multitudes of people

were consumed to bring silver and mercury to the surface in the

mines of Huancavelica and Potosi. In Eastern Europe, we have a

"second serfdom," tying to the land a population of farmers who had

I never previously been enserfed.9 In Western Europe, we have the

Enclosures, the Witch Hunt, the branding, whipping, and

incarceration of vagabonds and beggars in newly constructed work-

houses and correction houses, models for the future prison system.

On the horizon, we have the rise of the slave trade, while on the

seas, ships are already transporting indentured servants and

convicts from Europe to America.

10.I am echoing here Marx's statement in Capital, Vol. 1:

"Force... is in itself an economic power" (1909: 824). Far less

convincing is Marx's accompanying observation, according to

which: "Force is the midwife of every old society pregnant with a

new one" (ibid.). First, midwives bring life into the world, not

destruction. This metaphor also suggests that capitalism

"evolved" out of forces gestating in the bosom of the feudal world

— an assumption which Marx himself refutes in his discussion of

primitive accumulation. Comparing force to the generative

powers of a midwife also casts a benign veil over the process of

capital accumulation, suggesting necessity, inevitability, and

ultimately, progress.

What we deduce from this scenario is that force was the main lever,

the main economic power in the process of primitive accumulation10

because capitalist development required an immense leap in the

wealth appropriated by the European ruling class and the number of

workers brought under its command. In other words, primitive

accumulation consisted in an immense accumulation of labor-power

— "dead labor" in the form of stolen goods, and "living labor" in the

form of human beings made available for exploitation — realized on

a scale never before matched in the course of history.

Significantly, the tendency of the capitalist class, during the first three

centuries of its existence, was to impose slavery and other forms of

coerced labor as the dominant work relation, a tendency limited only

by the workers' resistance and the danger of the exhaustion of the

work-force.

11. Slavery had never been abolished in Europe, surviving in

pockets, mostly as female domestic slavery. But by the end of

the 15th century slaves began to be imported again, by the

Portuguese, from Africa. Attempts to impose slavery continued in

England through the 16th century, resulting (after the introduction

of public relief) in the construction of work-houses and correction

houses, which England pioneered in Europe.

This was true not only in the American colonies, where, by the 16th

century, economies based on coerced labor were forming, but in

Europe as well. Later, I examine the importance of slave-labor and

the plantation system in capitalist accumulation. Here I want to

stress that in Europe, too, in the 15th century, slavery, never

completely abolished, was revitalized.11

As reported by the Italian historian Salvatore Bono, to whom we owe

the most extensive study of slavery in Italy, there were numerous

slaves in the Mediterranean areas in the 16th and 17th centuries,

and their numbers grew after the Battle of Lepanto (1571) that

escalated the hostilities against the Muslim world. Bono calculates

that more than 10,000 slaves lived in Naples and 25,000 in the

Napolitan kingdom as a whole (one per cent of the population), and

similar figures apply to other Italian towns and to southern France. In

Italy, a system of public slavery developed whereby thousands of

kidnapped foreigners — the ancestors of today's undocumented

immigrant workers — were employed by city governments for public

works, or were farmed out to private citizens who employed them in

agriculture. Many were destined for the oars, an important source of

such employment being the Vatican fleet (Bono 1999:6-8).

Footnotes 12 to 16

12. See, on this point, Samir Amin (1974). To stress the

existence of European slavery in the 16th and 17th centuries

(and after) is also important because this fact has been often

"forgotten" by European historians. According to Salvatore Bono,

this self-induced oblivion was a product of the "Scramble for

Africa," which was justified as a mission aimed to terminate

slavery on the African continent. Bono argues that Europe's

elites could not admit to having employed slaves in Europe, the

alleged cradle of democracy.

13. Immanuel Wallerstein (1974), 90-95; Peter Kriedte (1978),

69-70.

14. Paolo Thea (1998) has powerfully reconstructed the history

of the German artists who sided with the peasants.

During the Protestant Reformation some among the best 16th-century

German artists abandoned their laboratories to join the peasants in struggle....

They drafted documents inspired by the principles of evangelic poverty, the common sharing of goods, and the redistribution of wealth. Sometimes... they took

arms in support of the cause.The endless list of those who, after the military defeats

of May-June 1525, met the rigors of the penal code, mercilessly applied by the

winners against the vanquished, includes famous names. Among them are [Jorg]

Ratget quartered in Pforzheim (Stuttgart), [Philipp] Dietman beheaded, and

[Tilman] Riemenschneider mutilated — both in Wurzburg — [Matthias]

Grunewald chased from the court of Magonza where he worked. Holbein the

Young was so troubled by the events that he fled from Basel, a city that was torn

apart by religious conflict.” [My translation]

Also in Switzerland, Austria, and the Tyrol artists participated in the Peasant War, including famous ones like Lucas Cranach (Cranach the old) as well as myriad lesser painters and engravers (ibid.: 7). Thea points out that the deeply felt participation of the artists to the cause of the peasants is also demonstrated by the revaluation of rural themes depicting peasant life — dancing peasants, animals, and flora — in contemporary 16th-century German art (ibid.:12-15; 73,79,80).“The countryside had become animated... [it] had acquired in the uprising a personality worth of being represented” (ibid.: 155). [My translation],

15. It was through the prism of the Peasant War and Anabaptism

that the European governments, through the 16th and 17th

centuries, interpreted and repressed every form of social protest.

The echoes of the Anabaptist revolution were felt in Elizabethan

England and in France, inspiring utmost vigilance and severity

with regard to any challenge to the constituted authority.

"Anabaptist" became a cursed word, a sign of opprobrium and

criminal intent, as "communist" was in the United States in the

1950s, and "terrorist" is today.

16. Village authority and privileges were maintained in the

hinterland of some city-states. In a number of territorial states,

the peasants "continued to refuse dues, taxes, and labor

services"; "they let me yell and give me nothing," complained the

abbot of Schussenried, referring to those working on his land

(Blickle 1985: 172). In Upper Swabia (southwest Germany),

though serfdom was not abolished, some of the main peasant

grievances relating to inheritance and marriage rights were

accepted with the Treaty of Memmingen of 1526. “On the Upper

Rhine, too, some areas reached setdements that were positive

for the peasants” (ibid.:172-174). In Switzerland, in Bern and

Zurich, serfdom was abolished. Improvements in the lot of the

“common man” were negotiated in Tyrol and Salzburg (ibid.: 176-

179). But “the true child of the revolution” was the territorial

assembly, instituted after 1525 in Upper Swabia, providing the

foundation for a system of self-government that remained in

place till the 19th century. New territorial assemblies emerged

after 1525 “[realizing] in a weakened form one of the demands of

1525: that the of common man ought to be part of the territorial

estates alongside the nobles, the clergy, and the towns." Blickle

concludes that “Wherever this cause won out, we cannot say

that there the lords crowned their military conquest with political

victory, [as] the prince was still bound to the consent of the

common man. Only later, during the formation of the absolute

state, did the prince succeed in freeing himself from that

consent”(ibid.: 181-182).

Slavery is "that form [of exploitation] towards which the master

always strives" (Dockes 1982: 2). Europe was no exception. This

must be emphasized to dispel the assumption of a special

connection between slavery and Africa.12 But in Europe slavery

remained a limited phenomenon, as the material conditions for it did

not exist, although the employers' desires for it must have been quite

strong if it took until the 18th century before slavery was outlawed in

England. The attempt to bring back serfdom failed as well, except in

the East, where population scarcity gave landlords the upper

hand.13 In the West its restoration was prevented by peasant

resistance culminating in the "German Peasant War." A broad

organizational effort spreading over three countries (Germany,

Austria, Switzerland) and joining workers from every field (farmers,

miners, artisans, including the best German and Austrian artists),14

this "revolution of the common man" was a watershed in European

history. Like the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, it shook the

powerful to the core, merging in their consciousness with the

Anabaptists takeover of Munster, which confirmed their fears that an

international conspiracy was underway to overthrow their power.15

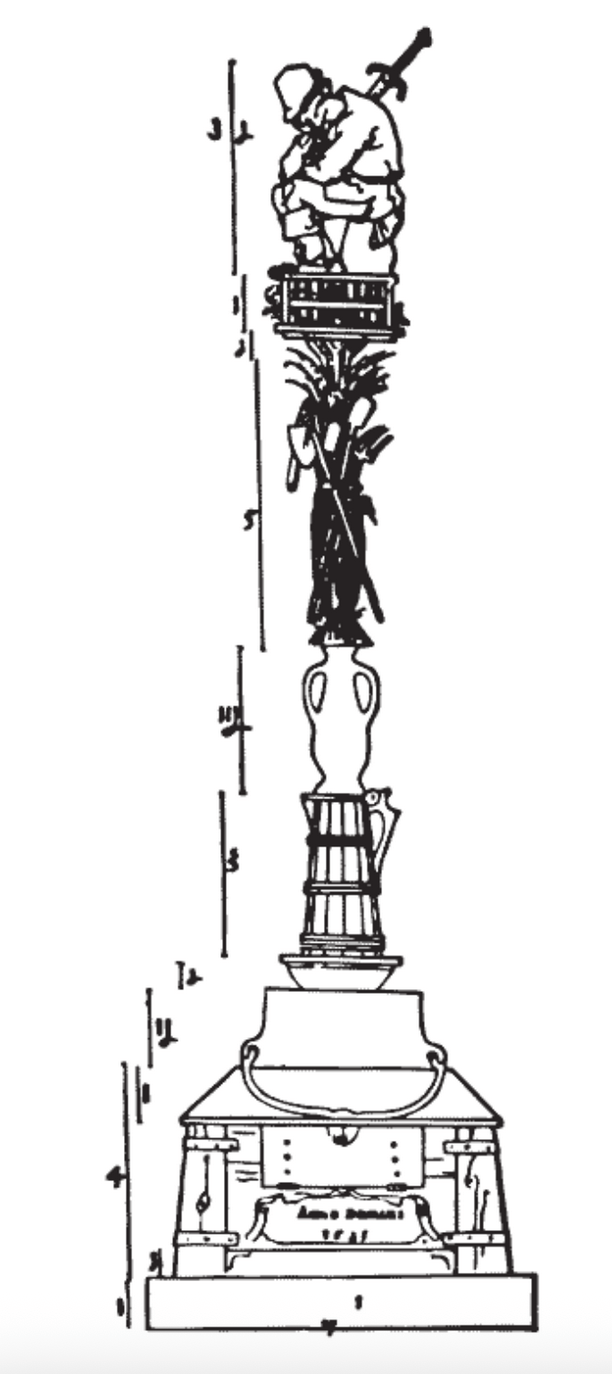

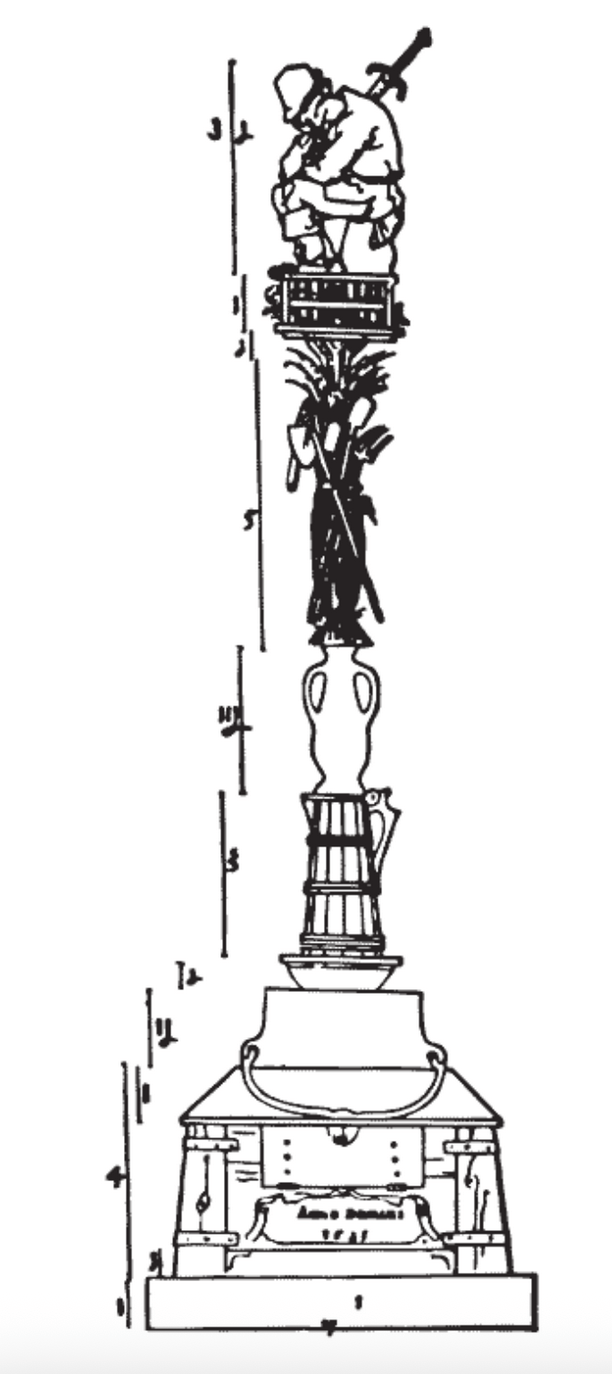

After its defeat, which occurred in the same year as the conquest of

Peru, and which was commemorated by Albrecht Differ with the

"Monument to the Vanquished Peasants" (Thea 1998:65; 134-35),

the revenge was merciless. "Thousands of corpses laid on the

ground from Thuringia to Alsace, in the fields, in the woods, in the

ditches of a thousand dismantled, burned castles," "murdered,

tortured, impaled, martyred" (ibid.: 153,146). But the clock could not

be turned back. In various parts of Germany and the other territories

that had been at the center of the "war," customary rights and even

forms of territorial government were preserved.16

Footnotes 17 & 18

17. Referring to the growing pauperization brought about across

the world by capitalist development, the French anthropologist

Claude Meillassoux, in Maidens, Meal and Money (1981), has

argued that this contradiction spells a future crisis for capitalism:

“In the end imperialism — as a means of reproducing cheap

labor power — is leading capitalism to a major crisis, for even if

there are still millions of people in the world... not directly

involved in capitalist employment... how many are still capable

owing to the social disruption, famine and wars it brings about, of

producing their own subsistence and feeding their children?”

(1981:140).

18. The extent of the demographic catastrophe caused by “the

Columbian Exchange” is still debated. Estimates of the

population decline in South and Central America, in the first post-Columbian century, range widely, but contemporary scholarly

opinion is almost unanimous in likening its effects to an American

Holocaust. Andre Gunder Frank writes that: “Within little more

than a century, the Indian population declined by ninety percent

and even ninety-five percent in Mexico, Peru, and some other

regions” (1978: 43). Similarly, Noble David Cook argues that:

“Perhaps 9 million people resided within the limits delineated by

Peru’s contemporary boundaries.The number of inhabitants

remaining a century after contact was roughly a tenth of those

that were there when the Europeans invaded the Andean world”

(Cook 1981:116).

This was an exception. Where workers' resistance to re-enserfment

could not be broken, the response was the expropriation of the

peasantry from its land and the introduction of forced wage-labor.

Workers attempting to hire themselves out independently or leave

their employers were punished with incarceration and even with

death, in the case of recidivism. A "free" wage labor-market did not

develop in Europe until the 18th century, and even then, contractual

wage-work was obtained only at the price of an intense struggle and

by a limited set of laborers, mostly male and adult. Nevertheless, the

fact that slavery and serfdom could not be restored meant that the

labor crisis that had characterized the late Middle Ages continued in

Europe into the 17th century, aggravated by the fact that the drive to

maximize the exploitation of labor put in jeopardy the reproduction of

the work-force. This contradiction — which still characterizes

capitalist development17 — exploded most dramatically in the

American colonies, where work, disease, and disciplinary

punishments destroyed two thirds of the native American population

in the decades immediately after the Conquest.18 It was also at the

core of the slave trade and the exploitation of slave labor. Millions of

Africans died because of the torturous living conditions to which they

were subjected during the Middle Passage and on the plantations.

Never in Europe did the exploitation of the work-force reach such

genocidal proportions, except under the Nazi regime. Even so, there

too, in the 16th and 17th centuries, land privatization and the

commodification of social relations (the response of lords and

merchants to their economic crisis) caused widespread poverty,

mortality, and an intense resistance that threatened to shipwreck the

emerging capitalist economy. This, I argue, is the historical context in

which the history of women and reproduction in the transition from

feudalism to capitalism must be placed; for the changes which the

advent of Capitalism introduced in the social position of women —

especially at the proletarian level, whether in Europe or America —

were primarily dictated by the search for new sources of labor as

well as new forms of regimentation and division of the work-force.

Albrect Durer, Monument to the Vanquished Peasants. (1526).

This picture, representing a peasant enthroned on a collection of

objects from his daily life, is highly ambigious. It can suggest that

the peasants were betrayed or that they themslves should be

treated as traitors. Accordingly, it has been interpreted either as

a satire of the rebel peasants or as a homage to their moral

strength. What we know with certainty is that Durer was

profoundly perturbed by the events of 1525, and, as a convinced

Lutheran, must have followed Luther in his condemnation of the

revolt.

Albrect Durer, Monument to the Vanquished Peasants. (1526).

This picture, representing a peasant enthroned on a collection of

objects from his daily life, is highly ambigious. It can suggest that

the peasants were betrayed or that they themslves should be

treated as traitors. Accordingly, it has been interpreted either as

a satire of the rebel peasants or as a homage to their moral

strength. What we know with certainty is that Durer was

profoundly perturbed by the events of 1525, and, as a convinced

Lutheran, must have followed Luther in his condemnation of the

revolt.

In support of this statement, I trace the main developments that

shaped the advent of capitalism in Europe — land privatization and

the Price Revolution — to argue that neither was sufficient to

produce a self-sustaining process of proletarianization. I then

examine in broad outlines the policies which the capitalist class

introduced to discipline, reproduce, and expand the European

proletariat, beginning with the attack it launched on women, resulting

in the construction of a new patriarchal order, which I define as the

"patriarchy of the wage." Lastly, I look at the production of racial and

sexual hierarchies in the colonies, asking to what extent they could

form a terrain of confrontation or solidarity between indigenous,

African, and European women and between women and men.

Land Privatisation in Europe, the Production of

Scarcity, and the Separation of Production from

Reproduction

From the beginning of capitalism, the immiseration of the working

class began with war and land privatization.This was an international

phenomenon. By the mid-16th century European merchants had

expropriated much of the land of the Canary Islands and turned them

into sugar plantations. The most massive process of land

privatization and enclosure occurred in the Americas where, by the

turn of the 17th century, one-third of the communal indigenous land

had been appropriated by the Spaniards under the system of the

encomienda. Loss of land was also one of the consequences of

slave-raiding in Africa, which deprived many communities of the best

among their youth.

In Europe land privatization began in the late-15th century,

simultaneously with colonial expansion. It took different forms: the

evictions of tenants, rent increases, and increased state taxation,

leading to debt and the sale of land. I define all these forms as land

expropriation because, even when force was not used, the loss of

land occurred against the individual's or the community's will and

undermined their capacity for subsistence. Two forms of land

expropriation must be mentioned: war — whose character changed

in this period, being used as a means to transform territorial and

economic arrangements — and religious reform.

"[B]efore 1494 warfare in Europe had mainly consisted of minor wars

characterized by brief and irregular campaigns" (Cunningham and

Grell 2000: 95). These often took place in the summer to give the

peasants, who formed the bulk of the armies, the time to sow their

crops; armies confronted each other for long periods of time without

much action. But by the 16th century wars became more frequent

and a new type of warfare appeared, in part because of

technological innovation but mostly because the European states

began to turn to territorial conquest to resolve their economic crisis

and wealthy financiers invested in it. Military campaigns became

much longer. Armies grew tenfold, and they became permanent and

professionalized. Mercenaries were hired who had no attachment

to the local population; and the goal of warfare became the

elimination of the enemy, so that war left in its wake deserted

villages, fields covered with corpses, famines, and epidemics, as in

Albrecht Differs "The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse" (1498).

This phenomenon, whose traumatic impact on the population is

reflected in numerous artistic representations, changed the

agricultural landscape of Europe.

19

20

Jaques Callot, The Horros of War (1633), Engraving. The men

hanged by military authorities were former soldiers turned

robbers. Dismissed soldiers were a large part of the vagabonds

and beggars that crowded the roads of 17th-century Europe.

Many tenure contracts were also annulled when the Church's lands

were confiscated in the course of the Protestant Reformation, which

began with a massive land-grab by the upper class. In France, a

common hunger for the Church's land at first united the lower and

higher classes in the Protestant movement, but when the land was

auctioned, starting in 1563, the artisans and day-laborers, who had

demanded the expropriation of the Church "with a passion born of

bitterness and hope," and had mobilized with the promise that they

too would receive their share, were betrayed in their expectations

(Le Roy Ladurie 1974:173—76). Also the peasants, who had

become Protestant to free themselves from the tithes, were

deceived. When they stood by their rights, declaring that "the Gospel

promises land freedom and enfranchisement," they were savagely

attacked as fomenters of sedition (ibid.: 192). In England as well,

much land changed hands in the name of religious reform. W. G.

Hoskin has described it as "the greatest transference of land in

English history since the Norman Conquest" or, more succinctly, as

"The Great Plunder." In England, however, land privatization was

mostly accomplished through the "Enclosures," a phenomenon that

has become so associated with the expropriation of workers from

their "common wealth" that, in our time, it is used by anti-capitalist

activists as a signifier for every attack on social entitlements.

21

22

23

In the 16th century, "enclosure" was a technical term, indicating a set

of strategies the English lords and rich farmers used to eliminate

communal land property and expand their holdings. It mostly

referred to the abolition of the open-field system, an arrangement by

which villagers owned non-contiguous strips of land in a non-hedged

field. Enclosing also included the fencing off of the commons and the

pulling down of the shacks of poor cottagers who had no land but

could survive because they had access to customary rights. Large

tracts of land were also enclosed to create deer parks, while entire

villages were cast down, to be laid to pasture.

Though the Enclosures continued into the 18th century (Neeson

1993), even before the Reformation, more than two thousand rural

communities were destroyed in this way (Fryde 1996:185). So

severe was the extinction of rural villages that in 1518 and again in

1548 the Crown called for an investigation. But despite the

appointment of several royal commissions, little was done to stop the

trend. What began, instead, was an intense struggle, climaxing in

numerous uprisings, accompanied by a long debate on the merits

and demerits of land privatization which is still continuing today,

revitalized by the World Bank's assault on the last planetary

commons.

Briefly put, the argument proposed by "modernizers," from all

political perspectives, is that the enclosures boosted agricultural

efficiency, and the dislocations they produced were well

compensated by a significant increase in agricultural productivity. It

is claimed that the land was depleted and, if it had remained in the

24

25

hands of the poor, it would have ceased to produce (anticipating

Garret Hardin's "tragedy of the commons") , while its takeover by

the rich allowed it to rest. Coupled with agricultural innovation, the

argument goes, the enclosures made the land more productive,

leading to the expansion of the food supply. From this viewpoint, any

praise for communal land tenure is dismissed as "nostalgia for the

past," the assumption being that agricultural communalism is

backward and inefficient, and that those who defend it are guilty of

an undue attachment to tradition.

But these arguments do not hold. Land privatization and the

commercialization of agriculture did not increase the food supply

available to the common people, though more food was made

available for the market and for export. For workers they inaugurated

two centuries of starvation, in the same way as today, even in the

most fertile areas of Africa, Asia, and Latin America, malnutrition is

rampant due to the destruction of communal land-tenure and the

"export or perish" policy imposed by the World Bank's structural

adjustment programs. Nor did the introduction of new agricultural

techniques in England compensate for this loss. On the contrary, the

development of agrarian capitalism "worked hand in glove" with the

impoverishment of the rural population (Lis and Soly 1979: 102). A

testimony to the misery produced by land privatization is the fact

that, barely a century after the emergence of agrarian capitalism,

sixty European towns had instituted some form of social assistance

or were moving in this direction, and vagabondage had become an

international problem (ibid.: 87). Population growth may have been a

26

27

contributing factor; but its importance has been overstated, and

should be circumscribed in time. By the last part of the 16th century,

almost everywhere in Europe, the population was stagnating or

declining, but this time workers did not derive any benefit from the

change.

There are also misconceptions about the effectiveness of the open-

field system of agriculture. Neo-liberal historians have described it as

wasteful, but even a supporter of land privatization like Jean De

Vries recognizes that the communal use of agricultural fields had

many advantages. It protected the peasants from harvest failure, due

to the variety of strips to which a family had access; it also allowed

for a manageable work-schedule (since each strip required attention

at a different time); and it encouraged a democratic way of life, built

on self-government and self-reliance, since all decisions — when to

plant or harvest, when to drain the fens, how many animals to allow

on the commons — were taken by peasant assemblies.28

Rural feast. All the festivals, games, and gatherings of the

peasant community were held on the commons. 16th-century

engravings by Daniel Hopfer.

The same considerations apply to the "commons." Disparaged in

16th century literature as a source of laziness and disorder, the

commons were essential to the reproduction of many small farmers

or cottars who survived only because they had access to meadows

in which to keep cows, or woods in which to gather timber, wild

berries and herbs, or quarries, fish-ponds, and open spaces in which

to meet. Beside encouraging collective decision-making and work

cooperation, the commons were the material foundation upon which

peasant solidarity and sociality could thrive. All the festivals, games,

and gatherings of the peasant community were held on the

commons. The social function of the commons was especially

important for women, who, having less title to land and less social

power, were more dependent on them for their subsistence,

autonomy, and sociality. Paraphrasing Alice Clark's statement about

the importance of markets for women in pre-capitalist Europe, we

can say that the commons too were for women the center of social

life, the place where they convened, exchanged news, took advice,

and where a women's viewpoint on communal events, autonomous

from that of men, could form (Clark 1968:51).

This web of cooperative relations, which R.D.Tawney has referred to

as the "primitive communism" of the feudal village, crumbled when

the open-field system was abolished and the communal lands were

fenced off (Tawney 1967). Not only did cooperation in agricultural

labor die when land was privatized and individual labor contracts

replaced collective ones; economic differences among the rural

population deepened, as the number of poor squatters increased

who had nothing left but a cot and a cow, and no choice but to go

with "bended knee and cap in hand" to beg for a job (Seccombe

1992). Social cohesion broke down; families disintegrated, the

youth left the village to join the increasing number of vagabonds or

29

30

itinerant workers — soon to become the social problem of the age —

while the elderly were left behind to fend for themselves. Particularly

disadvantaged were older women who, no longer supported by their

children, fell onto the poor rolls or survived by borrowing, petty theft,

and delayed payments .The outcome was a peasantry polarized not

only by the deepening economic inequalities, but by a web of hatred

and resentments that is well-documented in the records of the witch-

hunt, which show that quarrels relating to requests for help, the

trespassing of animals, or unpaid rents were in the background of

many accusations.

The enclosures also undermined the economic situation of the

artisans. In the same way in which multinational corporations take

advantage of the peasants expropriated from their lands by the

World Bank to construct "free export zones" where commodities are

produced at the lowest cost, so, in the 16th and 17th centuries,

merchant capitalists took advantage of the cheap labor-force that

had been made available in the rural areas to break the power of the

urban guilds and destroy the artisans' independence.This was

especially the case in the textile industry that was reorganized as a

rural cottage industry, and on the basis of the "putting out" system,

the ancestor of today's "informal economy," also built on the labor of

women and children. But textile workers were not the only ones

whose labor was cheapened. As soon as they lost access to land, all

workers were plunged into a dependence unknown in medieval

times, as their landless condition gave employers the power to cut

31

32

their pay and lengthen the working-day. In Protestant areas this

happened under the guise of religious reform, which doubled the

work-year by eliminating the saints' days.

Not surprisingly, with land expropriation came a change in the

workers' attitude towards the wage. While in the Middle Ages wages

could be viewed as an instrument of freedom (in contrast to the

compulsion of the labor services), as soon as access to land came to

an end wages began to be viewed as instruments of enslavement

(Hill 1975:181ff) .

Such was the hatred that workers felt for waged labor that Gerrard

Winstanley, the leader of the Diggers, declared that it that it did not

make any difference whether one lived under the enemy or under

one's brother, if one worked for a wage.This explains the growth, in

the wake of the enclosures (using the term in a broad sense to

include all forms of land privatization), of the number of "vagabonds"

and "masterless" men, who preferred to take to the road and to risk

enslavement or death — as prescribed by the "bloody" legislation

passed against them —rather than to work for a wage. It also

explains the strenuous struggle which peasants made to defend their

land from expropriation, no matter how meager its size.

In England, anti-enclosure struggles began in the late 15th century

and continued throughout the 16th and 17th, when leveling the

enclosing hedges became "the most common species of social

protest" and the symbol of class conflict (Manning 1988:311). Anti-

enclosure riots often turned into mass uprisings. The most notorious

33

34

was Kett's Rebellion, named after its leader, Robert Kett, that took

place in Norfolk in 1549.This was no small nocturnal affair. At its

peak, the rebels numbered 16,000, had an artillery, defeated a

government army of 12,000, and even captured Norwich, at the time

the second largest city in England. They also drafted a program

that, if realized, would have checked the advance of agrarian

capitalism and eliminated all vestiges of feudal power in the country.

It consisted of twenty-nine demands that Kett, a farmer and tanner,

presented to the Lord Protector. The first was that "from henceforth

no man shall enclose any more." Other articles demanded that rents

should be reduced to the rates that had prevailed sixty-five years

before, that "all freeholders and copy holders may take the profits of

all commons," and that "all bond-men may be made free, for god

made all free with his precious blood sheddying" (Fletcher 1973:

142-44). These demands were put into practice. Throughout Norfolk,

enclosing hedges were uprooted, and only when another

government army attacked them were the rebels stopped.Thirty-five

hundred were slain in the massacre that followed. Hundreds more

were wounded. Kett and his brother William were hanged outside

Norwich's walls.

Anti-enclosure struggles continued, however, through the Jacobean

period with a noticeable increase in the presence of women.

During the reign of James I, about ten percent of enclosure riots

included women among the rebels. Some were all female protests.

In 1607, for instance, thirty-seven women, led by a "Captain

Dorothy" attacked coal miners working on what women claimed to

35

36

be the village commons in Thorpe Moor (Yorkshire). Forty women

went to "cast down the fences and hedges" of an enclosure in

Waddingham (Lincolnshire) in 1608; and in 1609, on a manor of

Dunchurch (Warwickshire) "fifteen women, including wives, widows,

spinsters, unmarried daughters, and servants, took it upon

themselves to assemble at night to dig up the hedges and level the

ditches" (ibid.: 97). Again, at York in May 1624, women destroyed an

enclosure and went to prison for it — they were said to have

"enjoyed tobacco and ale after their feat" (Fraser 1984: 225—

26).Then, in 1641, a crowd that broke into an enclosed fen at

Buckden consisted mainly of women aided by boys (ibid.). And these

were just a few instances of a confrontation in which women holding

pitchforks and scythes resisted the fencing of the land or the draining

of the fens when their livelihood was threatened.

This strong female presence has been attributed to the belief that

women were above the law, being "covered" legally by their

husbands. Even men, we are told, dressed like women to pull up the

fences. But this explanation should not be taken too far. For the

government soon eliminated this privilege, and started arresting and

imprisoning women involved in anti-enclosure riots. Moreover, we

should not assume that women had no stake of their own in the

resistance to land expropriation. The opposite was the case.

As with the commutation, women were those who suffered most

when the land was lost and the village community fell apart. Part of

the reason is that it was far more difficult for them to become

vagabonds or migrant workers, for a nomadic life exposed them to

37

male violence, especially at a time when misogyny was escalating.

Women were also less mobile on account of pregnancies and the

caring of children, a fact overlooked by scholars who consider the

flight from servitude (through migration and other forms of

nomadism) the paradigmatic forms of struggle. Nor could women

become soldiers for pay, though some joined armies as cooks,

washers, prostitutes, and wives; but by the 17th century this

option too vanished, as armies were further regimented and the

crowds of women that used to follow them were expelled from the

battlefields (Kriedte 1983:55).

Women were also more negatively impacted by the enclosures

because as soon as land was privatized and monetary relations

began to dominate economic life, they found it more difficult than

men to support themselves, being increasingly confined to

reproductive labor at the very time when this work was being

completely devalued. As we will see, this phenomenon, which has

accompanied the shift from a subsistence to a money-economy, in

every phase of capitalist development, can be attributed to several

factors. It is clear, however, that the commercialization of economic

life provided the material conditions for it.

With the demise of the subsistence economy that had prevailed in

pre-capitalist Europe, the unity of production and reproduction which

has been typical of all societies based on production-for-use came to

an end, as these activities became the carriers of different social

relations and were sexually differentiated. In the new monetary

regime, only production-for-market was defined as a value-creating

38

activity, whereas the reproduction of the worker began to be

considered as valueless from an economic viewpoint and even

ceased to be considered as work. Reproductive work continued to

be paid — though at the lowest rates — when performed for the

master class or outside the home. But the economic importance of

the reproduction of labor-power carried out in the home, and its

function in the accumulation of capital became invisible, being

mystified as a natural vocation and labeled "women's labor." In

addition, women were excluded from many waged occupations and,

when they worked for a wage, they earned a pittance compared to

the average male wage.

Entitled "Women and Knaves," this picture by Hans Sebald

Beham (c. 1530) shows the train of women that used to follow

the armies even to the battlefield. The women, including wives

and prostitutes, took care of the reproduction of the soldiers.

Notice the woman wearing a muzzling device.

These historic changes — that peaked in the 19th century with the

creation of the full-time housewife — redefined women's position in

society and in relation to men.The sexual division of labor that

emerged from it not only fixed women to reproductive work, but

increased their dependence on men, enabling the state and

employers to use the male wage as a means to command women's

labor. In this way, the separation of commodity production from the

reproduction of labor-power also made possible the development of

a specifically capitalist use of the wage and of the markets as means

for the accumulation of unpaid labor.

Most importantly, the separation of production from reproduction

created a class of proletarian women who were as dispossessed as

men but, unlike their male relatives, in a society that was becoming

increasingly monetarized, had almost no access to wages, thus

being forced into a condition of chronic poverty, economic

dependence, and invisibility as workers.

As we will see, the devaluation and feminization of reproductive

labor was a disaster also for male workers, for the devaluation of

reproductive labor inevitably devalued its product: labor-power. But

there is no doubt that in the "transition from feudalism to capitalism"

women suffered a unique process of social degradation that was

fundamental to the accumulation of capital and has remained so

ever since.

Also in view of these developments, we cannot say, then, that the

separation of the worker from the land and the advent of a money-

economy realized the struggle which the medieval serfs had fought

to free themselves from bondage. It was not the workers — male or

female — who were liberated by land privatization. What was

"liberated" was capital, as the land was now "free" to function as a

means of accumulation and exploitation, rather than as a means of

subsistence. Liberated were the landlords, who now could unload

onto the workers most of the cost of their reproduction, giving them

access to some means of subsistence only when directly employed.

When work would not be available or would not be sufficiently

profitable, as in times of commercial or agricultural crisis, workers,

instead, could be laid off and left to starve.

The separation of workers from their means of subsistence and their

new dependence on monetary relations also meant that the real

wage could now be cut and women's labor could be further devalued

with respect to men's through monetary manipulation. It is not a

coincidence, then, that as soon as land began to be privatized, the

prices of foodstuffs, which for two centuries had stagnated, began to

rise.

The Price Revolution and the Pauperisation of the

European Working Class

39

This "inflationary" phenomenon, which due to its devastating social

consequences has been named the Price Revolution (Ramsey

1971), was attributed by contemporaries and later economists

(e.g.,Adam Smith) to the arrival of gold and silver from America,

"pouring into Europe [through Spain] in a mammoth stream"

(Hamilton 1965: vii). But it has been noted that prices had been

rising before these metals started circulating through the European

markets. Moreover, in themselves, gold and silver are not capital,

and could have been put to other uses, e.g., to make jewelry or

golden cupolas or to embroider clothes. If they functioned as price-

regulating devices, capable of turning even wheat into a precious

commodity, this was because they were planted into a developing

capitalist world, in which a growing percentage of the population —

one-third in England (Laslett 1971:53) — had no access to land and

had to buy the food that they had once produced, and because the

ruling class had learned to use the magical power of money to cut

labor costs. In other words, prices rose because of the development

of a national and international market-system encouraging the

export-import of agricultural products, and because merchants

hoarded goods to sell them later at a higher price. In September

1565, in Antwerp, "while the poor were literally starving in the

streets," a warehouse collapsed under the weight of the grain

packed in it (Hackett Fischer 1996:88).

It was under these circumstances that the arrival of the American

treasure triggered a massive redistribution of wealth and a new

proletarianization process. Rising prices ruined the small farmers,

40

41

who had to give up their land to buy grain or bread when the

harvests could not feed their families, and created a class of

capitalist entrepreneurs, who accumulated fortunes by investing in

agriculture and money-lending, at a time when having money was for

many people a matter of life or death.

The Price Revolution also triggered a historic collapse in the real

wage comparable to that which has occurred in our time throughout

Africa, Asia, and Latin America, in the countries "structurally

adjusted" by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

By 1600, real wages in Spain had lost thirty percent of their

purchasing power with respect to what they had been in 1511

(Hamilton 1965:280), and the collapse was just as sharp in other

countries. While the price of food went up eight times, wages

increased only by three times (Hackett Fischer 1996:74).This was

not the work of the invisible hand of the market, but the product of a

state policy that prevented laborers from organizing, while giving

merchants the maximum freedom with regard to the pricing and

movement of goods. Predictably, within a few decades, the real

wage lost two-thirds of its purchasing power, as shown by the

changes that intervened in the daily wages of an English carpenter,

expressed in kilograms of grain, between the 14th and 18th century

(SlicherVan Bath 1963:327):

42

Years Kilograms of Grain

1351-1400 121.8

1401-1450 155.1

1451-1500 143.5

1500-1550 122.4

1551-1600 83.0

1601-1650 48.3

1651-1700 74.1

1701-1750 94.6

1751-1800 79.6

It took centuries for wages in Europe to return to the level they had

reached in the late Middle Ages.Things deteriorated to the point that,

in England, by 1550, male artisans had to work forty weeks to earn

the same income that, at the beginning of the century, they had been

able to obtain in fifteen weeks. In Fran, [see graph, next page]

wages dropped by sixty percent between 1470 and 1570 (Hackett

Fischer 1996:78). The wage collapse was especially disastrous for

women. In the 14th century, they had received half the pay of a man

for the same task; but by the mid-16th century they were receiving

only one-third of the reduced male wage, and could no longer

support themselves by wage-work, neither in agriculture nor in

manufacturing, a fact undoubtedly responsible for the massive

spread of prostitution in this period. What followed was the

43

44

absolute impoverishment of the European working class, a

phenomenon so widespread and general that, by 1550 and long

after, workers in Europe were referred to as simply "the poor."

Evidence for this dramatic impoverishment is the change that

occurred in the workers' diets. Meat disappeared from their tables,

except for a few scraps of lard, and so did beer and wine, salt and

olive oil (Braudel 1973:127ff; Le Roy Ladurie 1974). From the 16th to

the 18th centuries, the workers' diets consisted essentially of bread,

the main expense in their budget. This was a historic setback

(whatever we may think of dietary norms) compared to the

abundance of meat that had typified the late Middle Ages. Peter

Kriedte writes that at that time, the "annual meat consumption had

reached the figure of 100 kilos per person, an incredible quantity

even by today's standards. Up to the 19th century this figure

declined to less than twenty kilos" (Kriedte 1983: 52). Braudel too

speaks of the end of" carnivorous Europe," summoning as a witness

the Swabian Heinrich Muller who, in 1550, commented that,

...in the past they ate differently at the peasant's house. Then,

there was meat and food in profusion every day; tables at village

fairs and feasts sank under their load. Today, everything has truly

changed. For some years, in fact, what a calamitous time, what

high prices! And the food of the most comfortably off peasants is

almost worse than that of day-labourers and valets previously"

(Braudel 1973:130).

Not only did meat disappear, but food shortages became common,

aggravated in times of harvest failure, when the scanty grain

reserves sent the price of grain sky-high, condemning city dwellers

to starvation (Braudel 1966,Vol. 1:328).This is what occurred in the

famine years of the 1540s and 1550s, and again in the decades of

the 1580s and 1590s, which were some of the worst in the history of

the European proletariat, coinciding with widespread unrest and a

record number of witch-trials. But malnutrition was rampant also in

normal times, so that food acquired a high symbolic value as a

marker of rank. The desire for it among the poor reached epic

proportions, inspiring dreams of Pantagruelian orgies, like those

described by Rabelais in his Gargantua and Pantagruel (1552), and

causing nightmarish obsessions, such as the conviction (spread

among northeastern Italian farmers) that witches roamed the

countryside at night to feed upon their cattle (Mazzali 1988:73).

Price Revolution and the Fall of the Real Wage, 1480-1640. The

Price REvolution triggered a historic collapse in the real wage.

Within a few decades, the real wage lost two-thirds of its

purchasing power. The real wage did not return to the level it had

readched in the 15th century until the 19th century (Phelps-

Brown and Hopkins, 1981).

The social consequence of the Price Revolution are revealed by

these charts, which indicate, respectively, the rise in the price of

grain in England between 1490 and 1650, the concomitant rise in

prices and property crimes in Essex (England) between 1566

and 1602, and the population decline measured in millions in

German, Austria, Italy and Spain between 1500 and 1750

(Hackett Fischer, 1996).

Indeed, the Europe that was preparing to become a Promethean

world-mover, presumably taking humankind to new technological

and cultural heights, was a place where people never had enough to

eat. Food became an object of such intense desire that it was

believed that the poor sold their souls to the devil to get their hands

on it. Europe was also a place where, in times of bad harvests,

country-folk fed upon acorns, wild roots, or the barks of trees, and

multitudes roved the countryside weeping and wailing, "so hungry

that they would devour the beans in the fields" (Le Roy Ladurie

1974); or they invaded the cities to benefit from grain distributions or

to attack the houses and granaries of the rich who, in turn, rushed to

get arms and shut the city gates to keep the starving out (Heller

1986:56-63).

That the transition to capitalism inaugurated a long period of

starvation for workers in Europe — which plausibly ended because

of the economic expansion produced by colonization — is also

demonstrated by the fact that, while in the 14th and 15th centuries,

the proletarian struggle had centered around the demand for "liberty"

and less work, by the 16th and 17th, it was mostly spurred by

hunger, taking the form of assaults on bakeries and granaries, and of

riots against the export of local crops. The authorities described

those who participated in these attacks as "good for nothing" or

"poor"and "humble people," but most were craftsmen, living, by this

time, from hand to mouth.

45

It was the women who usually initiated and led the food revolts. Six

of the thirty-one food riots in 17th-century France studied by Ives-

Marie Berce were made up exclusively of women. In the others the

female presence was so conspicuous that Berce calls them

"womens riots." Commenting on this phenomenon, with reference

to 18th-century England, Sheila Rowbotham concluded that women

were prominent in this type of protest because of their role as their

families' caretakers. But women were also those most ruined by high

prices for, having less access to money and employment than men,

they were more dependent on cheap food for survival.This is why,

despite their subordinate status, they took quickly to the streets

when food prices went up, or when rumor spread that the grain

supplies were being removed from town.This is what happened at

the time of the Cordoba uprising of 1652, which started "early in the

morning ... when a poor woman went weeping through the streets of

the poor quarter, holding the body of her son who had died of

hunger" (Kamen 1971: 364). The same occurred in Montpellier in

1645, when women took to the streets "to protect their children from

starvation" (ibid.: 356). In France, women besieged the bakeries

when they became convinced that grain was to be embezzled, or

found out that the rich had bought the best bread and the remaining

was lighter or more expensive. Crowds of poor women would then

gather at the bakers' stalls, demanding bread and charging the

bakers with hiding their supplies. Riots broke out also in the squares

where grain markets were held, or along the routes taken by the

carts with the corn to be exported, and "at the river banks

where...boatmen could be seen loading the sacks" On these

46

occasions the rioters ambushed the carts... with pitchforks and

sticks... the men carrying away the sacks, the women gathering as

much grain as they could in their skirts" (Berce 1990:171-73).

The struggle for food was fought also by other means, such as

poaching, stealing from one's neighbors' fields or homes, and

assaults on the houses of the rich. In Troyes in 1523, rumor had it

that the poor had put the houses of the rich on fire, preparing to

invade them (Heller 1986:55-56). At Malines, in the Low Countries,

the houses of speculators were marked by angry peasants with

blood (Hackett Fischer 1996:88). Not surprisingly, "food crimes" loom

large in the disciplinary procedures of the 16th and 17th centuries.

Exemplary is the recurrence of the theme of the "diabolical banquet"

in the witch-trials, suggesting that feasting on roasted mutton, white

bread, and wine was now considered a diabolic act in the case of the

"common people." But the main weapons available to the poor in

their struggle for survival were their own famished bodies, as in

times of famine hordes of vagabonds and beggars surrounded the

better off, half-dead of hunger and disease, grabbing their arms,

exposing their wounds to them and, forcing them to five in a state of

constant fear at the prospect of both contamination and revolt. "You

cannot walk down a street or stop in a square — a Venetian man

wrote in the mid-16th century — without multitudes surrounding you

to beg for charity: you see hunger written on their faces, their eyes

like gemless rings, the wretchedness of their bodies with skins

shaped only by bones" (ibid.: 88). A century later, in Florence, the

scene was about the same."[I]t was impossible to hear Mass," one

G. Balducci complained, in April 1650, "so much was one

importuned during the service by wretched people naked and

covered with sores" (Braudel 1966,Vol. II: 734-35).

Family of vagabonds. Engraving by Lucas van Leyden, 1520.

47

The State Intervention in the Reproduction of

Labor: Poor Relief, and the Criminalization of the

'Working Class

The struggle for food was not the only front in the battle against the

spread of capitalist relations. Everywhere masses of people resisted

the destruction of their former ways of existence, fighting against

land privatization, the abolition of customary rights, the imposition of

new taxes, wage-dependence, and the continuous presence of

armies in their neighborhoods, which was so hated that people

rushed to close the gates of their towns to prevent soldiers from

settling among them.

In France, one thousand "emotions" (uprisings) occurred between

the 1530s and 1670s, many involving entire provinces and requiring

the intervention of troops (Goubert 1986:205). England, Italy, and

Spain present a similar picture, indicating that the pre-capitalist

world of the village, which Marx dismissed under the rubric of "rural

isolation,"could produce as high a level of struggle as any the

industrial proletariat has waged.

In the Middle Ages, migration, vagabondage, and the rise of "crimes

against property" were part of the resistance to impoverishment and

dispossession; these phenomena now took on massive proportions.

Everywhere — if we give credit to the complaints of the

contemporary authorities — vagabonds were swarming, changing

cities, crossing borders, sleeping in the haystacks or crowding at the

gates of towns — a vast humanity involved in a diaspora of its own,

48

that for decades escaped the authorities' control. Six thousand

vagabonds were reported in Venice alone in 1545. "In Spain

vagrants cluttered the road, stopping at every town" (Braudel, Vol. II:

740). Starting with England, always a pioneer in these matters, the

state passed new, far harsher anti-vagabond laws prescribing

enslavement and capital punishment in cases of recidivism. But

repression was not effective and the roads of 16th and 17th-century

Europe remained places of great (com)motion and

encounters.Through them passed heretics escaping persecution,

discharged soldiers, journeymen and other "humble folk" in search of

employment, and then foreign artisans, evicted peasants, prostitutes,

hucksters, petty thieves, professional beggars. Above all, through

the roads of Europe passed the tales, stories, and experiences of a

developing proletariat. Meanwhile, the crime rates also escalated, in

such proportions that we can assume that a massive reclamation

and reappropriation of the stolen communal wealth was underway.

Today, these aspects of the transition to capitalism may seem (for

Europe at least) things of the past or — as Marx put it in the

Grundrisse (1973:459) "historical preconditions" of capitalist

development, to be overcome by more mature forms of capitalism.

But the essential similarity between these phenomena and the social

consequences of the new phase of globalization that we are

witnessing tells us otherwise. Pauperization, rebellion, and the

escalation of "crime"are structural elements of capitalist

accumulation as capitalism must strip the work-force from its means

of reproduction to impose its own rule.

49

50

Vagrant being whipped through the streets.

That in the industrializing regions of Europe, by the 19th century, the

most extreme forms of proletarian misery and rebellion had

disappeared is not a proof against this claim. Proletarian misery and

rebellions did not come to an end; they only lessened to the degree

that the super-exploitation of workers had been exported, through

the institutionalization of slavery, at first, and later through the

continuing expansion of colonial domination.

As for the "transition" period, this remained in Europe a time of

intense social conflict, providing the stage for a set of state initiatives

that, judging from their effects, had three main objectives: (a) to

create a more disciplined work-force; (b) to diffuse social protest;

and (c) to fix workers to the jobs forced upon them. Let us look at

them in turn.

In pursuit of social discipline, an attack was launched against all

forms of collective sociality and sexuality including sports, games,

dances, ale-wakes, festivals, and other group-rituals that had been a

source of bonding and solidarity among workers. It was sanctioned

by a deluge of bills: twenty-five, in England, just for the regulation of

alehouses, in the years between 1601 and 1606 (Underdown 1985:

47-48). Peter Burke (1978), in his work on the subject, has spoken of

it as a campaign against "popular culture." But we can see that what

was at stake was the desocialization or decollectivization of the

reproduction of the work-force, as well as the attempt to impose a

more productive use of leisure time.This process, in England,

reached its climax with the coming to power of the Puritans in the

aftermath of the Civil War (1642—49), when the fear of social

indiscipline prompted the banning of all proletarian gatherings and

merrymaking. But the "moral reformation" was equally intense in

non-Protestant areas where, in the same period, religious

processions were replacing the dancing and singing that had been